2: Who Goes There?

What can I hear on the MW band

So you are interested in the MW band and would like to know what you can hear

The Medium Wave (MW) band is an internationally agreed band of frequencies primarily set aside for the purpose of broadcasting. It has been used worldwide for 100 years and is occupied by thousands of radio stations. It is still heavily used in the 21st century despite many stations moving to digital broadcasting or going online.

Officially the band is defined as 526.5 kHz – 1606.5 kHz in Europe and up to 1705kHz in North America. But you will also find signals of interest both above and below the nominal band limits. What sorts of signals can you hear on the MW band?

International broadcasters

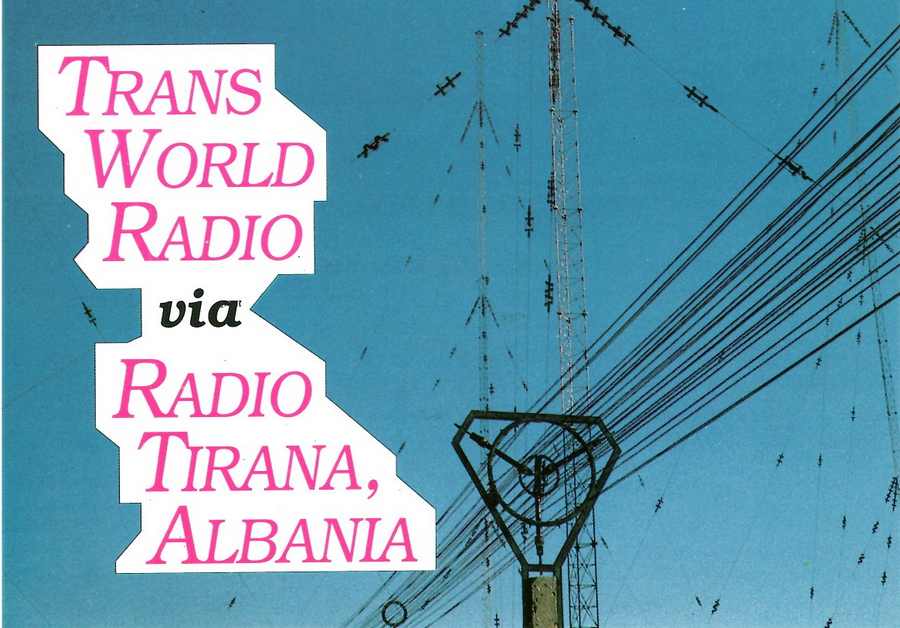

Although true international broadcasting uses shortwave frequencies on account of the distance signals will travel, the MW band has been used extensively for “cross-border” broadcasting. The cause is often political or commercial. One of the earliest proponents of this was Radio Luxembourg which served all of Europe and not just the Grand Duchy. The first boom occurred in Mexico with high powered commercial “border blasters” like XERF transmitting into the USA. Then there was the 1960s boom in offshore pirate radio, most famously Radio Caroline. In parallel there was the Cold War proliferation of high power propaganda stations mainly broadcasting over the Iron Curtain. Examples included Radio Moscow, Stimme der DDR, Radio Free Europe and many more. You could also find religious radio stations like Trans World Radio operating to evangelise over large territories via MW radio.

The heyday of MW international broadcasting was prior to the fall of the Berlin Wall, but you will still find examples today. For the DXer they are good targets because they often are high powered and designed to get a signal out over a large area.

Regional broadcasters

These used to be best exemplified by the Clear Channel stations in North America. These 50000 Watt stations had the exceptional privilege of having a MW channel virtually to themselves. This was a deliberate move to ensure that the vast rural interior could get good radio reception at night when coverage of half the continental USA is typical. Although some stations still operate as de facto clear channel stations, they no longer have an automatic right to use their frequency exclusively.

Synchronised networks

These are networks of several stations all on one frequency carrying the same programme set up specifically to provide national coverage. Since broadcasting in many countries is operated by the state or the ministry of information this gave homogenous programming across a whole nation.

Such networks need care in their design and operation to avoid problems with carrier frequency synchronisation and variable delay in the distribution of audio to each transmitter. The most notable examples of synchronised networks are run by the BBC in the UK for distribution of Radio 5 Live, the news and sports network. The network operated by Absolute Radio on 1215kHz, also in the UK, is less successful.

From a DXers point of view these networks become interesting if certain transmitters switch over briefly to local programming giving the listener a chance to get a local identification.

Local broadcasters

By far the majority of stations on the MW band fall into this category, characterised by the co-location of the station, its studios and transmitter and its audience. Transmitter powers can range from as little as 1W to 100kW or more, depending on the coverage area and the degree of co-channel interference. Many local broadcasters in North America operate only during daylight hours in order to avoid problems with co-channel interference brought in by the night-time sky-wave.

In recent year stations have moved from true localism to centralised programme creation to cut costs. To maintain the illusion of localism identification and advertising and sometimes traffic & weather are kept as local inserts into otherwise networked programming.

In some markets truly local broadcasters have merged into large broadcasting conglomerates with no local presence apart from the transmitter. This trend started in the 1970s and has accelerated to the present day.

However another group of local broadcasters has appeared in some countries since the turn of the century and that is low powered stations (typically 1-50 watts) serving very small areas (e.g hospitals, universities etc).

Navigational beacons

Radio signals are an essential means of navigating for most ships and aeroplanes and the frequencies between the Long Wave band and the MW band have been allocated for this purpose. More surprisingly, a few beacons operate in the MW band interspersed amongst the broadcasters. Beacons are usually low power and intended to give accurate navigational information over 50-100 nautical miles range, however long distance listeners (DXers) will be able to detect the repetitive Morse code identification messages from beacons over much greater distances. Although traditional non-directional beacons are less used these days, there has been growth in transmitters for differential GPS systems.

Clandestines, pirates and jammers

Most signals described so far are more or less permanent features in the MW landscape. However, there are several more transient types of signals which can be heard, the most prominent of which are pirates and clandestine operations. Pirates are stations operating openly without official licences from any country. They range from one time hobby pirates operating from someone’s bedroom to fully financed operations broadcasting from ships at sea. The heyday of the seaborne pirate seems to be gone since the likes of Radio Caroline, Voice of Peace and Radio New York International have passed into the history books. However land based pirates have persisted since the 1960s in a number of countries (UK & Netherlands in particular).

Clandestine stations are usually politically motivated broadcasters often supported by a covert government operation. Operations are complex since stations can pretend to be what they are not and there is always the possibility of the double bluff! These stations come and go, reflecting political changes in their ‘host’ country. Currently the bulk of known clandestines are operating in the Middle East. Long serving examples include National Radio of the Saharan Democratic Republic (since 1975).

Clandestine stations, as well as official broadcasters, are often the target of jamming if the government in the area targeted by the broadcaster feels threatened by the message being carried. Jamming usually takes the form of a powerful transmitter broadcasting irritating noise and interference on the same frequency as the station beaming into the country. Jamming on MW has fallen dramatically since the late 1980s and now is confined mainly to the Middle East and the Korean peninsula.

Long Wave stations

Though the Long Wave (LW) band (148.5 – 283.5kHz) is not strictly part of the MW Band, many listeners have common interest in the two bands. Long Wave is only used by broadcasters in Europe, North Africa, Mongolia and the Asian part of the former Soviet Union. Elsewhere in the world these frequencies are used mainly by navigational beacons similar to those found between 283.5 and 525kHz. One exception is in the USA where 160-190kHz is also used by experimenters who are allowed just 1W of power to tiny antenna!

In recent years many LW stations have fallen silent due to declining audiences and increasing maintenance costs. A few transmitters have remained for strategic purposes – during the Cold War it was said that if a British submarine surfaced and could not receive the BBC on 198kHz it meant that the UK had been wiped out by nuclear war.

Other occupants

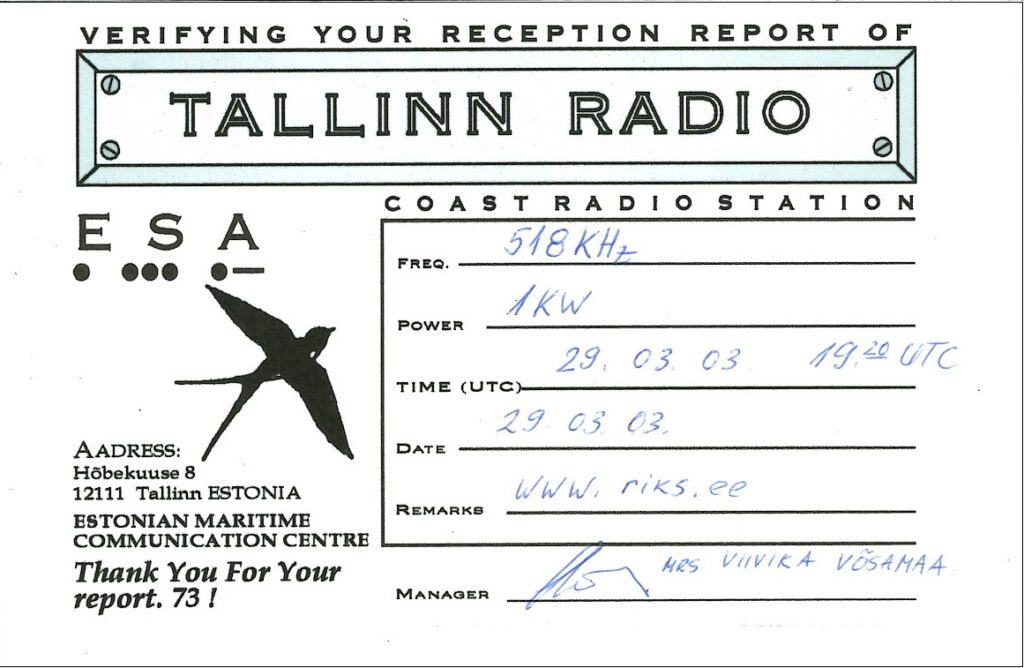

Loosely coupled to the main broadcast frequencies you will find a number of other interesting signals.. The frequencies of 518 and 490kHz are used worldwide for Navtex, a maritime information broadcasting system for shipping. These are digital transmissions but easy to decode with the right equipment or software.

Above 1600kHz in Europe you will find coastal radio stations in several countries broadcasting weather and other maritime information. These operate in SSB mode and for brief scheduled broadcasts. You’ll likely hear digital military communications and may even stumble across some relic first generation cordless phones in FM mode. And finally below the MW band at 472-479kHz you’ll find the 630m amateur band. From time to time other mysterious signals appear (such as driftnet buoy radio beacons), which is part of the fun of exploring the medium wave band.

There is plenty of choice for the MW DXer to chase after.